Soil of Serpentine

Winemaker Interview

Soil of Serpentine

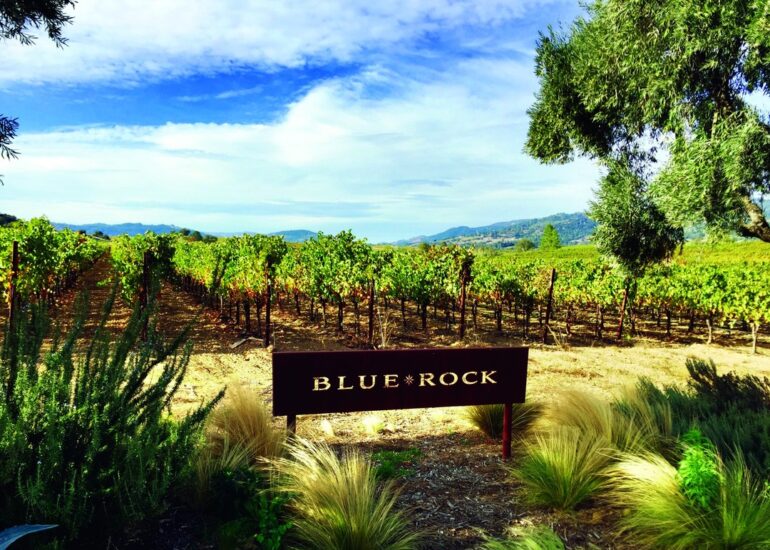

A conversation with Kenneth Kahn of Blue Rock Vineyard in Sonoma's Alexander Valley

Winery Entrepreneur Restores Site History, Seeks to Elevate Alexander Valley

An Interview with the Founder of Blue Rock Vineyard

The surface of Alexander Valley’s utmost potential as a wine region has barely been scratched. At least that’s the belief of a small cadre of local producers dedicated to crafting premium Bordeaux varietal wines — of whom one is particularly adamant in his determination to help realize that promise. Kenneth Kahn, the founder of Blue Rock Vineyard, while doing his own part to prove what this Sonoma appellation is truly capable of, is hoping that the efforts of its quality-driven producers will help to bring a new level of recognition to this region. With a respectful nod to the mid-priced wines that first earned the area media attention, Kahn nevertheless remains committed and driven to pushing the limit of its possibilities in an effort to demonstrate that Alexander Valley is capable of accomplishing so much more. I sat down with this bold entrepreneur to learn more about his vision for this wine region and how his brand Blue Rock fits into it.

As is typical of many winegrowing valleys, the hillsides are particularly noteworthy for their tendency to cultivate vines that bear high quality fruit. Though there are several reasons for this, in the case of the site on which Blue Rock Vineyard lies, there is a unique geological one: the soil’s prevalence of serpentine rock. High in magnesium and therefore prominently blue in color, it served to inspire the name of Kahn’s wine brand. More importantly, by virtue of its low moisture and nutritional content, the serpentine soil forces the vines to struggle and therefore focus on producing grapes of remarkable aromatics and concentration of fruit flavor. The properties of this soil, combined with Kahn’s unwavering dedication to invest in the most stringent and, at times, experimental viticultural techniques, have allowed him to produce ultra premium Bordeaux varietal wines in a region not well known for that style. He spoke candidly not only of the risks he has taken in realizing his dream, but also of how doing so has helped him grow considerably both professionally and personally.

— Nikitas Magel

Following are edited excerpts from the interview. At the bottom of this post is the full recording.

Manifesting the Dream

Nikitas Magel: What was your inspiration for starting a business in the wine industry?

Kenny Kahn: I really got into the business because I loved wine as a consumer. In the early ’80s, when I was in Memphis, I had a neighbor, an older man named Milton Picard. ‘Pic,’ as we called him, had been collecting Bordeaux and great California wine since the ’30s. His collection of wines got to the point where he couldn’t drink them all, so he had the choice to either sell them or drink them with other people. So, after he sort of tapped me on the shoulder and asked if I wanted to learn about wine, we would go over to his house and he’d pull out First Growth Bordeaux from the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. Some of them, I swear to you, had $2 price tags on them! And through that, he really turned me on to great wine. Right about the same time, my wife and I starting taking cooking classes together (although she was already a great cook). And it all just came together: the food, the wine, the lifestyle. Plus, I love design and my wife is a painter. Now, today, as a consumer, I still love wine. Making wine, I understand what goes into the process and I know the technologies, but I don’t let that get in the way of actually enjoying wines. I have a cellar that’s not a collector’s cellar, it’s a drinker’s cellar: I’ll buy off-vintages of Bordeaux, like 2004, because I’m going to drink them, not give them to my kids. I’ve also been drinking a lot of Italian wines, and really learning about Barolos and Barbarescos. Of course, I love California wines, but I drink much less California Cabernet than anything else, because I’m making it. I will drink it because I want to know what my peers are doing.

KK: But I also got into the wine business because it’s a creative outlet for me. While my wife and I were living in Memphis, we decided that we wanted to pursue this as a dream. It was my dream, really, more so than hers; her dream was to come out to California because she loved the environment here so much. So, in 1979 we decided on making the move. But it took a few years, since there were detours along the way — like children! — so we actually made the move in 1985. Then in 1998, Bank of New York bought the firm I was with, and I stayed with them for another five years. But the whole time I was there, I kept dreaming about Blue Rock! And it really got the point where, to be fair to them since I was spending so much of my energy on developing the vineyard and the winery and the business here, it became right for me to leave and pursue this full-time.

NM: This was a significant shift, then; it became your second career! How has that been for you, going from one to the other? — especially given that I can’t think of two more vastly different industries!

KK: There’s actually a great deal of similarity. A lot of people, on learning what’s involved, are surprised over the nature of the business in running a winery or managing a vineyard. For me, it was like a Ferrari shifting from second to third gear; it was really effortless. And that’s because I established Blue Rock in 1987: I started as a winegrower, developed the vineyards, and then sold grapes to other wineries while I worked full-time in the brokerage business [in San Francisco]. I had great consultants whom I was learning from and who were working with me in the vineyard. At that point, although it was a serious hobby, it was still part time; I would come out here on the weekends. But even when I decided to go full-time, I was able to transition over very easily, because it’s really very similar to what I was doing at Bank of New York: it’s a business that I’m running, which has a production side, sales, marketing, finance, and really all of the same elements that I dealt with in the brokerage business. It’s all about building relationships with customers and exceeding expectations. Other than the product itself, there’s really not that many differences.

NM: You were clearly very fortunate, because it sounds like there wasn’t a long or arduous period of adjustment.

KK: It was all planned! This has been a 25-year strategic plan that we implemented. Soon after we bought the property, we started to replant it. We then started dreaming about renovating the house and the winery, which were first built in 1880 and had been a complete wreck! So, I worked and made money to finance the restoration and replanting, which we did in phases, maintaining my job because it required a tremendous amount of cash to replant the vineyards, especially with the way we’re farming here. We sold grapes for many years to other wineries, so we had the opportunity to taste the fruit from this vineyard with the other wineries who were making the wine. In doing so, we learned that it was really unique and special. Then in 1999, we decided to go full-time, as per our long term plan. We hired Nick Goldschmidt who, at the time, was the head winemaker at Simi, so he knew Alexander Valley. And he also makes very elegant wines using a style of winemaking that I’m very attracted to as a consumer. When we made the wine, we did so on a virtual basis: we used our grapes but we took them over to Trentadue [Winery] down the road and did a custom crush there. But once we rebuilt the original 1880s-era winery here, after buying our own crush equipment, we were able to do everything here and have control over it ourselves.

NM: So, when you came to this property, there was already some history here — winemaking history!

KK: There was a winery here, called Villa Maria, that was built in 1880. The Italian immigrants who came here wanted to be close to the Italian-Swiss Colony, which is down the road in Asti, and were attracted to this general area. Even now, our neighbors are Seghesio, Pedroncelli, and a lot of other wineries that began with Italian families. When these immigrants moved here around 1880, they built the house and the garden with the bocci ball court, and then they built a winery they called Villa Maria. Not a whole lot is known about it, other than the fact that it was here and when Prohibition hit, they weren’t able to make it anymore. Some of the other families in the area, like the Seghesios, were able to stay and continue their businesses by selling their grapes to home winemakers (who could make up to 200 gallons a year) or to the Church for sacramental purposes. And so a lot of the families around here just eked out a living and more or less kept on going until Prohibition was over. But this one didn’t make it, so the property fell into ruin from neglect until I bought it in 1987 — the land was completely overgrown with weeds, there was no roof on either the winery or this house, and it was all just a complete wreck. Restoring it was a project!

NM: Speaking of project, you left from your former career in stock brokerage to start a new one in winemaking. In diving into it though, at least from the business aspect, a lot of it actually felt natural to you — understandably, since there are market-driven underpinnings to the selling of wine that you make. But how was the transition for you in terms of the grapegrowing and winemaking?

KK: It’s been a wonderful learning experience, because when I started this, I knew nothing about grapegrowing. When I bought the vineyard in 1987, I hired a vineyard management company. The young man who owned the company, Jack Florence, right out of U.C. Davis, was well-educated and enthusiastic. And I learned from him! I also learned from the guys who were out there doing the hard work — the pruning, the tractor driving, the spraying, and so on — just through observation. It’s remarkably complex the way that we farm today. When I got to a point where I felt I learned pretty much all I could learn from Jack Florence, I continued to go U.C. Davis for advanced courses in viticulture. And the university is fabulous, especially because it allows people who are running vineyards and wineries to take updated courses to continue to learn.

Now, recently I hired a viticultural consultant, Garrett Buckland, who is a partner at Premier Viticulture in Napa. And he brings an entirely different perspective to all of this. I brought him in because I wanted to farm in Alexander Valley just as the absolute top vineyards are done in Napa. So the question was, What happens if you take a property that has wonderful potential like Blue Rock and farm it with the technology of the best winegrowing properties? Since Garrett is a consultant to a number of those properties — Duckhorn, Araujo, Chateau Montelena, and few others — I’m learning from him how to farm here exactly the way they do at the top vineyards in Napa. And we’re really getting some sensational results!

Doubling Down

NM: In your efforts to drive quality and maximize potential in the wines, it sounds like you’re really pushing the envelope with the choices you’ve made in both the vineyard and the cellar. What are some of the specific ways in which you’ve done so?

KK: Well, to be honest, I really bet the ranch! When I replanted the vineyard, I hired the winegrowing team of Daniel Roberts and Alfred Kass. Daniel is a Ph.D. in plant science and worked for Kendall Jackson, overseeing all of their replantings until he went off on his own as a consultant. Alfred, who’s from Australia, is also a Ph.D., but in soil science. And together these guys asked me what I wanted to do: to grow the absolute highest quality but with low tonnage per acre, or to yield higher tonnage with not the best quality. My answer was obvious. Now, when I say I bet the ranch, I meant that I was betting against the odds — in Alexander Valley, the highest average price per ton is only about half of what it is for Napa. So, to make the decision to go for high quality and low tonnage here takes a real leap of faith, because what happens if you produce low tonnage and people are still only willing to pay you half of what they pay for Napa fruit?

On top of that, in order to get high quality in this particular vineyard, we had to plant at a very high vine density because of the magnesium that devigorates the vine. Each vine is small and produces a small amount of fruit and therefore, in order to get any kind of commercially viable yield at all, you have to plant at a very high vine density. And that’s very expensive, because you have more plants per acre that require more structure in terms of irrigation equipment and trellising, and more labor in terms of tractor passes and hand harvesting. So, compared to my neighbors, I have a vineyard that’s very expensive to plant and install, and yields low tonnage. The leap of faith is that we’ll get paid in proportion to all that. And we’re still waiting for that to happen! It’s scary as hell! I have lost a lot of sleep, because I’ve put so much money into it, and it’s a big gamble. At the moment, I (meaning Blue Rock) am the only buyer of the grapes from this vineyard who’s willing to pay what they’re worth.

In the vineyard, we have all of our own crews and do all of our own tractor work and hand labor. Most vineyards have custom farmers who come in with a hundred people who will do one operation, like leaf-pulling, and then do another operation with a whole different set of workers. But you don’t build a vine-by-vine relationship like that. Yet it’s important to do so, because the soils are very different; you can walk ten feet and the one vine will look very different than the last one. When you have a hundred guys come in, then everything is done the same way. Whereas when you have your own crew doing everything in the vineyard, they’re walking the same row every day and so they know to treat one vine differently from another. You want each vine to have balance. So, I think that our focus is more on the vineyard than on the actual winemaking in terms of how we’re making improvements every year.

But answering your question as to what we did that was really pushing the envelope, there was planting at high density, knowing we were going to get low tonnage. In addition to that, we planted clones that were very high risk, those that were not from certified virus-free vines. I decided on that because I wanted to get budwood from phenomenal vineyards and was willing to do so even with the risk that it could be diseased. For example, our Cabernet Franc budwood comes from [Bordeaux’s Château] Cheval Blanc. I got it through a tip from Daniel Roberts who had worked with Rex Geitner, the vineyard manager for Spring Mountain Vineyards who had, prior to that, spent some time working at Cheval Blanc. So, my Cabernet Franc is the Geitner clone from the very budwood he brought back with him from their best vines. The risk that I took with that is that it wasn’t virus-tested. If it actually does have any virus, it’s not necessarily the end of the vines, but it would really cut back on their productivity and quality. But so far, so good. And I’m very excited because [that Cabernet Franc] really is special! So those are all risks that I’ve been willing to take because I’m really pursuing the best that I can out here. And some of those risks don’t pay off; there were some parts of the vineyard that I had to replant because they did end up being virus-ridden.

NM: Did the Bordeaux varietals that you ultimately settled on for the wines of Blue Rock stem directly from the discoveries you made in the process of replanting?

KK: Absolutely! Now, when I bought the land, we originally had eleven different varietals planted in the vineyard: the Bordeaux five (Cabernets Sauvignon and Franc, Merlot, Petit Verdot, Malbec); Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Muscat, Viognier, Syrah, and a couple of others. Because in California, especially in an unknown area (as this was until relatively recently), you could plant whatever you like! But then, of course, not all of it worked. What we found was that the white varietals, especially, were not very distinctive here; they were okay, but it’s just too warm for some of them. Plus it was kind of a waste because the red Bordeaux varietals turned out so good, they just shined! And the Syrah I wanted to plant because I just love Syrah! {laughing} And we got lucky there because it actually does very well on this property — the budwood originally came from Château Beaucastel, my favorite Châteauneuf-du-Pape! It’s just a small amount, only two acres.

NM: How much of your original vineyard have you actually had to replant since you started ten years ago? Would you say there’s been a significant replanting, and if so, can you talk about the impact of that necessity on the overall business and direction of the brand?

KK: We’ve definitely had a significant replanting. As the younger vines come into production, we always vinify them separately and then make an analysis as to whether they make the grade or not. Based on that we actually started a second wine called Baby Blue that’s from the young vines — an artisan-production wine that’s from all estate-grown young vines and aged in all-French oak. Having said that, we do have one block of young vines that blows everything away and that goes into the Blue Rock wine. But my point is really that we make the decision to vinify everything separately. And several times throughout the year, we check in on the different cuvées. You can tell very early on whether something is going to make one grade vs. another. And so we actually have three grades of Cabernet Sauvignon. The first is our Best Barrel, which is extremely limited, made only in the best years, and amounts to only a couple of barrels. Our criteria for it is that it has to be both different and better than anything else, something that absolutely stands out.

The second is Blue Rock, which is our all-estate, flagship wine. It started out as 100% Cabernet Sauvignon, but it’s morphing since we might use some of the other Bordeaux varietals planted in the vineyard. We will blend if it really adds to the wine, but we don’t blend to be cute; we feel that the only reason to blend is if it really makes a better wine. For example, the 2005 Blue Rock Cabernet has 6% of the estate Malbec in it, which has a real blueberry note and a very Merlot-like texture that softens the Cabernet. Finally, the third level of our Cabernet is the Baby Blue that I mentioned. Baby Blue is an unbelievably serious Cabernet — but one that’s still at a very affordable price point. It’s being poured by the glass at Gramercy Tavern in New York, in addition to some other fantastic restaurants all over the country! And it’s been so well received by these restaurants because it’s affordable on the one hand, but still very serious on the other — it’s meant to blow away any by-the-glass restaurant wine.

Maximizing the Soil’s Potential

NM: Okay, so, two of your wines mention the color blue in their name. I recall that when I first tasted your wines, you said that there’s something very significant about the name Blue Rock and that it’s directly correlated to the wine’s style and character. Can you say more about the wine’s namesake?

KK: Well, first let me tell you about the process we went through before we settled on Blue Rock. Initially, my wife and I — the francophiles that we are — went through names like Clos this and Clos that, and the like. But none of it really stuck. When we bought the property, we bought it in foreclosure in 1987. And there was a number of reasons it was in foreclosure. First of all, the stock market had just crashed and there was, at least temporarily, a major recession. Also, Alexander Valley itself wasn’t very well known and so there weren’t any notable wineries in the area. We’re adjacent to Silver Oak Winery, but at the time even they weren’t well known. As a result, Alexander Valley fruit was not selling for very much. But the third reason that the property was in financial straits was that the land had a lot of serpentine rock [which is distinctly blue in color]. The neighboring farmers know that serpentine is high in magnesium and therefore very difficult to farm — you end up getting naturally very low tonnage from very wimpy vines that are really having to struggle. So, basically when this property was being sold at foreclosure, nobody showed up except me! And I was wild about the place, so absolutely in love with its beauty, that I had to contain myself from bidding against myself! {laughing} But seriously, no one else wanted the property!

Anyway, [the reason for the serpentine rock’s significance is that], as it turns out, the business model in 1987 was different from it is today. Back then, with its low market rates per ton of fruit, if you didn’t produce five, six, seven tons per acre in Alexander Valley, then you just couldn’t make any money. And that’s why this place was in foreclosure. Fortunately for me, though — and this was not by design, it was simply by good luck — the business model changed some years later, in that all of a sudden it became about quality, not quantity: a vineyard became valuable only if it was distinctive and if it produced something with power, finesse, balance, aromatics, and all the other things that people look for in upscale wines. It was now all about producing great wines. And you do that from properties that have a natural balance between the vigor of the vines and the amount of fruit that’s produced. It’s all about Goldilocks, really. Ideally, you want to have enough water because you have to be able to grow the canopy to ripen the fruit, but not too much water that would result in big canopies with vines that look like trees and grow fruit with vegetative flavors.

KK: Similarly, you have to have enough nutrition, but you don’t want to have deep, rich soils with too much nutrition because that grows too big of a crop with, again, too much canopy. The great vineyards of the world are exactly what Goldilocks would have wanted, with their perfect balance. When those vines produce the right amount of canopy, they basically just stop growing because they’ve exhausted the nutrition and the moisture in the soil, so there’s nothing in excess. So, now, one of the things that serpentine rock does, being very high in magnesium, is that it de-vigorates the vines. In fact, there are even areas where there’s actually too much serpentine and nothing will grow. But most of the vineyard, fortunately, has just the right amount of magnesium so that the vines can have just the perfect amount of growth without too much nutrition. What we get is relatively low tonnages of very intensely-perfumed fruit that has a really distinctive personality — it has black fruits, it has blue fruits, it has a mint quality — it really has a signature of its own.

NM: Yes, when I first tried your wines, I found them to be very fragrant. And that struck me because it’s not something I’ve found in own my experience to be typical with Bordeaux varietals, especially from this general region. I’m guessing that the aromatic signature of the wines comes from a cooling effect on the vineyard at night and in the early morning.

KK: I’m speculating with this, but I think it’s actually two things. Number one, it’s the soil; a lot of that perfumed quality comes again from the serpentine soils. And the other thing is that 45 degree [Fahrenheit] swing: at the peak of the day, it’s so hot that you’ll want to come into the house where it’s cool because of the stone walls, but then at night you’re wearing a sweater. It gets so cold at night, the vines just shut down. And terroir, which gives the wines their quality, is really all of those things combined: the amount of moisture, the aspect or angle to the sun, the temperature swings, the soil composition, etc.

Articulating the Appellation

NM: On the subject of terroir, it sounds like you believe that there’s a potential here in Alexander Valley that’s fully attainable and comparable to some of the best sites elsewhere that have earned reputations and continue to garner accolades. Granted, that’s already happening, to some extent, with a few of your neighbors. But you feel it can be taken a lot further.

KK: Well, we are getting recognition — just not so much from the media. And when I say media, I’m speaking namely of the big two, Robert Parker and the Wine Spectator. They like a certain style of wine: big, inky, alcoholic blockbusters. What we’re trying to produce is much more elegant, in part because that’s what God has given us in Alexander Valley. We have an average temperature swing of 45 degrees [Fahrenheit] between the high and low everyday. As a result, you get wines that retain a brightness with their fruit, have nice acidity, and are much more food friendly — wines in a style that these critics are not necessarily going to love.

Another part of the picture is that historically, Alexander Valley hasn’t been paid much to farm and to make wine at a very high level of quality. If you look at most of the producers here, they’re large, corporate wineries, and they’re producing wines at a price point anywhere from $10 to $20 a bottle. At those prices, they’re going to farm a pretty high tonnage of fruit per acre, they’re not going to use the best oak, and given those choices, they can only so much do to maximize the flavors they’re getting out of their vineyards.

But once you get out of the valley and into the hillsides, where we are, and if you’re driven to pay attention to details and willing to spend the money to do so, then you can get quality that’s equivalent to the absolute top properties in Napa. And I know that because I’ve submitted our wines into blind tastings with the top ones from Napa — and in those blind tastings, we’re always coming out ranking way up there against wines that are maybe two or three times the price. At the same time, we want to make sure we’re producing our own style of wine; we really want Blue Rock to be distinctly Alexander Valley, rather than something that could be confused for a Napa wine. There’s always a stylistic signature in Blue Rock and I’m happy about that! Because I think that if you’re going to make an all-estate wine, you’d better make something that’s distinctive and really stands on its own!

NM: Speaking standing on one’s own, how do you feel your wines are similar to those of your neighbors, and how do you feel they’re different?

KK: Funny you should ask that, because I’ve recently gathered together a little tasting group of artisan producers in Alexander Valley. See, most of the Cabernet produced in this valley is actually from corporate wineries who just aren’t doing the same thing that we’re trying to accomplish. I think they’re doing a great job at the price point where they are — but we’re aiming for much more artisanal wine production. And there are very few producers like that, though you’re already familiar with some of them: Garden Creek, Medlock Ames, Lancaster Estate, Goldschmidt Wines. So, with this group, I have had a chance to taste a number of the wines from this area, and I believe that there’s an Alexander Valley signature. But I don’t think the wine trade knows what it is because when I’m out in the marketplace, oftentimes people — sommeliers and retailers around the country — have an expectation; they’re expecting the wines to be vegetative. Yet when they taste our wines, they say, “Wow, there’s no ‘veg’ here, no green olive. These are fantastic wines; they’re balanced and elegant!”

So I think that what we small producers need to do is redefine what the common flavor profile of Alexander Valley is. And to answer your question more directly, yes, I do think there is a unique style here. In the wines we’re getting from the better sites and by the better producers — those who are committed to doing the best they can every year, some of whom I just mentioned — there is a real purity of flavor, a great deal of texture with early accessibility in the tannins, and because they’re well-made, a concentration of fruit and good balance, allowing them to age fantastically even though they’re drinkable early on. It’s the best of both worlds!

NM: But you feel that Alexander Valley still has a ways to go in carving out its identity as a wine region?

KK: Absolutely! And that’s because Alexander Valley doesn’t have the critical mass of small producers who are really committed to high quality, which is essential to portraying something recognizable. Whereas Napa has that. Napa has hundreds of small producers who are committed to that level of quality, giving you a prospect from each appellation as to what your expectation of their wines can be.

NM: Interestingly, then, what this all suggests is that at least historically, there have been attitudes among the trade and press about the wines of Alexander Valley that are based on an understanding of them which is skewed heavily towards a quality level of production far below what the region is capable of. And so, would you say this implies that those opinions are based on a misunderstanding?

KK: Well, I’m not sure that it’s a misunderstanding, per se. I think that Alexander Valley has actually been well received for what it has traditionally produced: really nice $10-$20 bottles of wine that are a good value. But those wines have certain characteristics that are different from those you can get from some of the more artisanal producers I mentioned, who are not in the deep soils of the valley floor, who farm their vineyards and make their wines to very high standards, who are extremely selective about which particular lots go into the bottle — characteristics that are just not well known because there are so few of us and our production has been so small thus far. How could they know? You almost have to get a James Laube or Robert Parker to come here and do a tasting of these six or seven wineries and then write about it in order for people to start understanding what can be done with real commitment at these better sites.

NM: Are you working towards that? {smiling}

KK: I’m working towards that. {smiling} In fact, Karin [Miller of Garden Creek Vineyards] and I are working on it. But it’s challenging — very challenging — because we producers have business agendas that are very different from one another. For example, the business plan for some of the wineries in the valley may be to drive consumers to their winery, whereas for others, like mine, who don’t have a tasting room, priorities are different. So, as far as formalizing it all and getting it funded, it’s very challenging; although people are really interested in it, it’s hard to get commitments in the midst of these divergent business interests.

Practicing Persistence

NM: Bringing it full circle and focusing on your own commitment, what have you learned that has profoundly influenced your appreciation of wine and your understanding of its industry? And what have you learned that has influenced you as a human being?

KK: Hmmm, that’s such an interesting question; I’ve never been asked that before. Well, I have to say that I love what I do! I dream about what I do when I’m not here. When I can’t sleep at night, I find myself walking up and down the vine rows, and before long I’m asleep; it’s like counting sheep! I guess what I’ve learned is that I’ve become much more spiritual. I’ve had to overcome a lot of obstacles! For example, last year, in a two-hour period we lost 75% of our crop due to frost. We walked out in the vineyard and there was nothing there, the shoots were all burned off like somebody took a blowtorch to them. I just felt like crying! But it is agriculture; there’s a lot of adversity to overcome in the vineyards. They always look great from a distance, from the road. Whereas when I look at it, I know what I’m looking at, I know about diseases like phylloxera, eutypa, and all the other things that can come to get you. So, it is about overcoming adversity. But when you walk into the vineyard on a day like today, and everything is healthy and prospering, you can’t help but have a spiritual experience! And I’m incredibly grateful! It makes me so very grateful for all the things that I have. I just don’t forget it when I walk out into the vineyard. Plus, we try to give back as a winery, in terms of being charitable, because we recognize how fortunate we are. Without getting grossly philosophical, I think that’s what I’ve learned more than anything else: to overcome adversity, stick with it, and then be really thankful for what you’ve got!

NM: Wow, that’s pretty powerful! And it’s also very elegant, because there’s a simplicity to that, which can be applied to anything that we do in our lives. That’s very inspiring!

KK: Well, I didn’t mean for it to be inspiring; it is what it is. It’s been wonderful for me, it’s been really wonderful. But it has also been such a tremendous challenge; there have been times I really thought I was going to go broke. And we’re not at all out of the woods yet. This is actually one of the most challenging times we’ve ever had.

NM: You’re quite a risk taker, then. Plain and simple. There is very little in your approach that’s safe.

KK: I’m an entrepreneur! I’m passionate about what I do. I hate to use the word ‘passion,’ because it no longer means anything these days, but I really do this because I love doing it!

Love, indeed. And that, along with inspiration, determination, and innovation, have provided Kenneth Kahn with the much-needed fuel for his entrepreneurial spirit, allowing him not only to realize his dream but quite possibly to be instrumental in the recognition of Alexander Valley as a source of premium handcrafted wines. Little did he know, upon starting his venture over twenty years ago, that breaking ground to plant a new vineyard would eventually lead him to breaking ground in furthering a winegrowing region. To learn more about his Blue Rock portfolio of wines and how to get them, visit Blue Rock Vineyard online.

Interview by Nikitas Magel

Photos by Blue Rock Vineyard

Comments are closed.