Mountain Majesty

Winemaker Interview

Mountain Majesty

A conversation with the talent behind Spring Mountain Vineyard in Napa Valley

Napa Winery Elaborates Two Styles of Cabernet from its Steep Hillside Vineyards

An Interview with the Talent Behind

Spring Mountain Vineyard

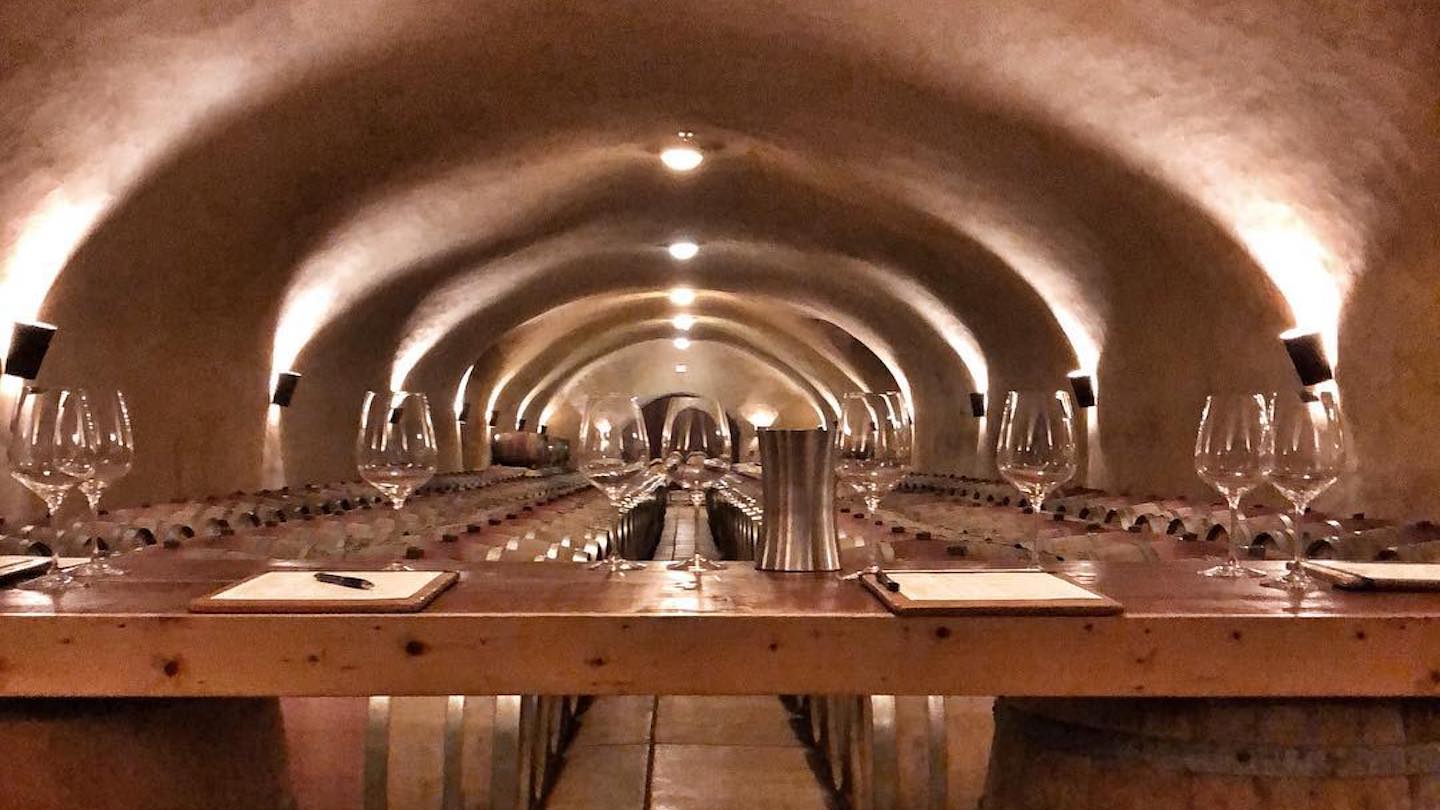

Grace and Complexity. Power and Intensity. These are the discrete expressions of Cabernet Sauvignon that we tend to associate respectively with the Old and New World. Yet one Napa Valley winery, in tapping the fullest potential of its mountainside grapevines, seems to have succeeded in articulating both. In doing so, Spring Mountain Vineyard, located on the eastern slope of the elevation bearing its name, has managed to carve a distinct niche for itself among the region’s numerous other quality-driven producers. Having been struck by the craftsmanship of its recent vintages, I resolved to peel back the label of this premium brand in an effort to get to the root of its winegrowing strategy. And so, in the context of a visit to the charmingly bucolic estate high above the town of St. Helena, I met with winemaker Jac Cole, vineyard manager Ron Rosenbrand, and publicist Valli Ferrell, who collectively showcased all that lends panache to the wines of Spring Mountain Vineyard.

Spanning a total of nearly 850 acres, Spring Mountain Vineyard’s estate is comprised of what were once three separate historical vineyards established in the late 1800s: Miravalle, La Perla, and Château Chevalier. In 1992, Swiss businessman Jacob Safra bought and combined the properties with the mission of crafting fine Cabernet-dominant wine in the tradition of Bordeaux. Today that wine is the elegant and seductive Elivette, the estate’s flagship, exquisitely elaborated from the property’s contiguous but vastly diverse patchwork of vineyards. It leads the portfolio of other mountain-grown wines, including the more recently added counterpoint of a bold and assertive California-style Cabernet. While touring the vineyards draped along the estate’s steep, rolling hillsides and tasting through the wines inside the Victorian Villa Miravalle’s grand salon, the winegrowing team relayed the story of what has come to define the brand to this day.

— Nikitas Magel

A Clear Vision: Expressing the Spring Mountain Identity

Nikitas Magel: You produce wines exclusively from Spring Mountain itself. But what is it that distinguishes wines produced from hillside fruit in general, and would you say they’re inherently superior to those from the valley floor?

Jac Cole: It’s a stylistic concept. Different people like different things in their wines. On the valley floor, you can accomplish more accessible wines earlier in their lifespans than you can on the mountains. The mountain fruit’s intrinsically tannic backbone is going to require a bit more aging before the wines soften and become as pliable and approachable as the stuff on the valley floor, which when released are very plush and delectable to people who like that style. If you prefer wines with more structure and capacity for aging, which then reach a higher peak in their maturation process, then mountain fruit is going to be what you want to look for. It really turns out to be a stylistic and personal preference. Our wines are as soft and lovely five years down the road as wines made from the valley floor — but they’re also much more complex, will last an extra ten years, and show much more dimension. If you’re looking for something to go with that steak on the grill, then maybe a valley floor wine is what you want. If you’re looking for something that’s a more intellectual approach to wine, then mountain fruit is going to give you the basis to be able to create that.

NM: So, it’s really a matter of taste and style preference, not quality. Could you then still generalize and say that wine from mountain fruit tends to age better and longer?

JC: Oh, absolutely! But it’s not only that they last longer — though it’s nice to know that if you have a ten year old wine made from mountain fruit then it’s going to be in good shape, while maybe one from the valley floor will likely be past its prime. Taking the idea that if you build a formula for making your wine, and the tannins and acid backbone from the mountain fruit allow you to add more time to that formula, my belief is that it will reach a higher peak than a wine that’s at its best right at the time of release. Not only do mountain wines themselves have greater longevity, but the complexity you get from aging (which younger wines don’t have) is an additional benefit. And you can only add that more time if the wines are structured.

These wines tend to be for the kind of person looking to collect and then enjoy wines at their peak. To give you an idea, the Bordelais model is a good one to look at. Those wines are tight at release, age beautifully, gradually open up, and then become much more magnificent as they put on more years. Wines made from mountain fruit are very much the same way. If you’re going to build a cellar, these are the kinds of wines you want to put in it. Now, Diamond Mountain has always been given that benediction; with Diamond Creek’s wines, nobody expects to pop a cork on one of those right at release, thinking they’ve got the world’s best wine. Spring Mountain has a very similar concept — we’re all on the same ridge, it’s all Mayacamas (Mount Veeder, Spring Mountain, Diamond Mountain). I do think our wines are a little less rustic than those of Diamond Mountain, at least historically; we have a tendency towards tannins that come into resolution a bit more quickly. But the fruit intensity — because of the concentration from the low amount of yield coming off the vineyards — I think is something that’s consistent all along the ridge. However, they are harder to make; the fruit is much more difficult to grow and there’s less tonnage coming out of the vineyards.

A Patchwork of Diversity: Developing Wines in the Vineyards

NM: Focusing on these vineyards, Ron, how would you describe the approach that you take in managing them to really maximize that flavor intensity in the resulting wines?

Ron Rosenbrand: What we’re trying to do here is have the vines in perfect balance between the canopy and the cropload. When a vine isn’t in good balance, some degree of flavor characteristics are going to suffer. So we aim to strike a good balance. If you grow grapes on the valley floor and have fifty pounds of fruit on a single plant, you’ve got to have an awful lot of canopy to support that cropload. On some blocks, you can do that, but balance is the key to achieving top quality — on any grapevine.

NM: Jac mentioned that the fruit is more difficult to grow. What are some of the challenges to farming on this mountain in general? And what are some of the difficulties you face specifically on this property that you feel are unique, as compared to other wine producers neighboring you on Spring Mountain?

RR: I think we all share a common challenge up here on Spring Mountain, and that applies to hillside farming in general: it’s much more difficult to farm up here than on the valley floor. There’s no question about that. There’s danger factors, like with rolling equipment over. There’s also erosion issues; a heavy rainfall can take out a vineyard and turn it into a mess in one single night. But comparing us to our neighbors, first off, our respective soil types are very different. Plus, I know that on top of Spring Mountain, there’s more of a plateau so they have deeper soils up there than we do…

JC: The thing that’s become vastly apparent to me is that, unlike all of our neighbors who have their vineyards at the very top, we have ours on the side of the mountain. We’re everything from the bottom of Spring Mountain District to about three-quarters of the way up the mountain. And so, we have the most sloped vineyards in the district, which gives us the greatest difficulties in managing them: the soil is much thinner here because the rainwater rolls off the top of the mountain and heads downhill, taking our soil with it. And since it’s been doing that for thousands of years, there’s not that much soil left — that’s our big challenge. Because when there’s no soil, there’s no water-holding capacity; even if you irrigate, the water runs right through it all and doesn’t stay for long. All of our neighbors, on the other hand, are on the ridge-top where the soils are much deeper, so they have no water problems like we do here. That being said, this also give us some benefits. What do we reap from this challenge? I frankly think that our fruit has much more intensity, in general. It does take a little more time to ripen, but when it does, it’s gorgeous!

NM: Speaking of gorgeous, you’re using a style of training in some of your vineyards that I’ve never seen before in California. Tell me about that!

RR: That training system is known as Vertical Gobelet. It’s very infrequently used mostly because people don’t understand it. But given how infertile the soil is here, the benefits to this system on our mountain is that we get great balance between crop and canopy. The choice in using this type of training stems back from when our owner bought the property and was trying to figure out how best to trellis and which varieties to plant. Being from Europe (he’s Swiss) and with a great affinity towards Burgundies and Bordeaux, he has a lot of French connections. One of those was a gentlemen by the name of Pierre Galet, a French viticultural expert, whom he flew over here to consult for him. Pierre said that this property very closely resembled the hills of the Rhône valley, and since Vertical Gobelet works so well in the Rhône, he suggested trying it here.

RR: And today we’re quite happy with the quality that comes from these vines. It was all part of the original research that our owner had done on the property to decide how the vineyards should be trellised. In fact, there’s a lot of different spacing on the property. Over on the Chevalier property, there are terraces that measure about 2 meters between the rows. Whereas these are 1×1 meter and planted very densely because the soil is shallow and not very fertile in this location — the roots don’t grow out far and compete with one another as they do with deeper loam soil. So, using Vertical Gobelet, we make the most efficient use of our ground here and maximize our potential cropload.

NM: The choice to implement a viticultural practice like this, entirely outside the local norm, is remarkable! What else are you doing in the vineyards, which you feel is unconventional and contributes directly to the quality of the wines?

RR: We’ve made a push towards growing 100% organically, and are in the process of getting certified Organic for our grape-growing. One of the things we’re doing differently from a lot of other producers, at least here on Spring Mountain, is that we use insects almost entirely to control our vineyards pests. We release over a million predatory and parasitic insects a year here, and they do a tremendous job! I use predatory mites for mite problems, ladybugs as a general consumer for many different types of insects, and then a couple of parasitic wasps for vine mealy bug. One of the last insects that I was having problems controlling without using insecticides was the blue-green sharpshooter [a vector for Pierce’s disease]. We discovered from talking with other folks that bluebirds do a great job in controlling sharpshooters. And so, we built over 650 bluebird houses and placed them throughout the vineyards. As a result, the bluebird population on the mountain has shot up tremendously — and the sharpshooter population has dropped off to almost nothing!

JC: We had great consulting help from UC Berkeley’s Entomology Department. And we ultimately found that we get better results and more control than when we used chemicals.

RR: Plus we’re building back the ecological balances of insects that had been wiped out over the years by the constant use of insecticides. Using those chemicals had eliminated a lot of the insects that were causing us problems, but it wiped out all the beneficial populations as well. So now we’re rebuilding those beneficial populations so that the natural ecosystem is working by itself. Another thing is that we stopped using herbicides a few years ago, so we’re building back the populations of soil microorganisms, earthworms, and the like, which were wiped out from years of herbicidal use. And I think it’s all making a huge difference in our ability to naturally grow grapes, by having all those organisms back in the soil. Plus, we’re using organic material for fertilizers, and basically moving our whole operation to an organic program that’s going to be better in the future for all of us.

JC: It’s better for the land, obviously. But it’s still with a focus on growing better grapes. A lot of times the word ‘struggle’ comes up when discussing growing conditions. Struggling is fine. Unhealthy is not. Too many people have in their mind that a vine needs to be small and weak, and which might produce maybe two bunches. What you really want are healthy plants struggling in a difficult environment in order to produce intensely flavored grapes. You need biological athletes — plants that are in great shape, thriving in challenging conditions — in order to make wonderful fruit. If they’re not in good shape, they produce imbalanced fruit that doesn’t ripen properly. And so, Ron’s aim is to grow healthy plants in struggling conditions.

A Tale of Two Styles: Weaving Elegance & Unleashing Power

NM: How does everything that you’ve described doing in the vineyards ultimately translate into the bottle? What’s the hallmark of the wines of Spring Mountain Vineyards; how do they stand out?

JC: The Spring Mountain Vineyards wines start out with a great deal of fruit, which given the amount of time necessary, then ages and evolves into something really special. But it’s the wines’ structure that carries them for a very long time. The elegance and balance of these wines gives them life now and longevity into the future, and the essence of the fruit coming off the mountain vineyards gives them character. And it’s beautiful fruit that ranges from the bright lively stuff you’ll see in our 2005 vintage to the evolved, almost pie-filling loveliness of what’s in the 2001 vintage. But again, it’s the structure — the tannins and acid — that gives you the time you need for all that to happen. So, these are wines with beauty and balance that are deeply appreciated with patience, and if you wait, you’ll be rewarded! Looking at their profiles, I think red [as opposed to black] fruit is always seriously part of our Cabernets’ character. Of course, you’ll find black currant flavors and pick up some anise and such, but I really think that red fruit is prominent, because of the acid maintenance that we have. Even though we have a great array of exposures in the vineyards, our principal exposure is easterly, so that means they’re shaded early in the day because of the steepness and that really preserves acid in the fruit, keeping it very lively. And then there’s a polish that we get in the tannins after a period of aging — they’re never harsh or overly angular. Now, I don’t know that any of this is completely unique, but it is a formula for great appreciation of wines that really show themselves five years down the line.

NM: You’ve alluded to the diversity of Cabernet fruit that you work with — a function of the patchwork of vineyards and their different aspects and elevations. Doesn’t that present a challenge to maintaining a single vision in your winemaking?

JC: It certainly does present some difficulty. It presented an even greater difficulty for me when I started, because at the time we were making two Bordeaux-style blends. We were trying to use all the same material, all the same base wines to produce two wines of the same stock. There wasn’t any way for me to put them together. But I did take what I considered to be the best base wines to produce our house style, and then the second best version of that style. Even so, I had a dilemma during the first year that I was here, because as I looked at the fifty-some base wines we had [from all the different vineyard blocks], not everything fit into the Elivette package; not everything we were making was Cabernet suitable for going into the Elivette. Some of it was too big, too bold, too round, and perhaps a bit too rustic to fit into the program of being a refined Bordeaux-style wine. And so, that’s when we convinced the owner that we should make a dedicated Cabernet separate from the Elivette. And that simplified my life entirely. It really opened the door because now, since the 2003 vintage, there are three wines types coming out of those fifty Cabernet base wines: an elegant, graceful, structured, complex, and ageable Cabernet [the Elivette]; a bold, direct, powerful, and more intensely Northern California approach to Cabernet [the SMV Cabernet]; and one that won’t fit into either and goes into our 2nd label, Chateau Chevalier.

NM: Can you describe the process of crafting these styles, and how you decide exactly which base wines goes into which of the two finished Cabernets?

JC: When I do my evaluation of the wines each year, I try to categorize them and put them into areas that they need to be in, and they naturally break apart into these two wines. The mindset you have to have when you make blends is that you’re putting together a couple of jigsaw puzzles: you know what the picture is supposed to look like, so when you pick up a piece, you know whether or not it’s going to fit into one picture or the other. But occasionally a piece it doesn’t really fit anywhere — a beautiful wine or a powerful wine that doesn’t fit into either one of my blends — so we’ll just bottle it up on its own and sell it in the wine club. Because when a [base] wine doesn’t mix in with any of the others, you have to leave it out, even though it’s a high quality wine.

Now, in general, when you try to make a Bordeaux blend [as opposed to a California Cabernet], it’s much more intricate, like a Swiss watch. It’s more difficult to put those elements together than to put together a bunch of bold Cabernets that like being together. There’s a simplicity to our Cabernet, but a complexity to our Elivette. From a winemaker’s perspective, it’s finely integrated and much more detailed to build a Bordeaux-style blend like the Elivette than it is to build a California Cabernet. Besides, the Cabernet in essence keeps saying, “I don’t want to be in your fine, elegant blend!”

NM: There’s a very prominent price differential between the two Cabernet wines you produce, suggesting that there’s a difference in quality. Is that really the case?

JC: That gets at another reason why we wanted to make [and position] a California Cabernet, specifically: so that it could find its way onto restaurant wine lists in the proper place. Prior to 2003, buyers had a tough time placing it when it was just the [lower-priced] estate Bordeax blend. In a case where both wines [as blends] ended up on a wine list, the only thing separating them was cost. And so a customer would wonder, “is one better than the other?”— No, that’s actually wrong; quality is not the issue. But when you stack them that way, quality looks like the issue. [Because of that, we replaced the lower-priced blend] with a California Cabernet whose quality is every bit as great as the Elivette — except that it’s a straight Cabernet and has a different style. There’s still a price differential between the two wines, but our intention is eventually to bring the Cabernet much closer in price to the Elivette. Because in the end, the two wines have the same quality of fruit, the same quality of production, the same quality of oak. Stylistically, though, they’re very different. With that said, there will probably always be just a bit of a price difference, because the Cabernet is not as difficult to assemble; it’s made up of bold, big flavors that just love to be together. Plus, we hold the Elivette back for a year longer before release, and that costs money.

Supporting Roles: Nodding to Burgundy & Northern Rhône

NM: In addition to the Cabernet and Elivette, there are some other highlights to the portfolio, one of which is the Sauvignon Blanc.

JC: The Sauvignon Blanc is a blend of two separate vineyards whose soils are very different. From one, we get flavors of melon and stone fruits, whereas with the other, we get more mineral character and citrus qualities. And so, we put the two together and then barrel ferment that. The idea is to take those two elements and blend them, bringing two concepts of Sauvignon Blanc together into one wine, along with just a little bit of Sémillon. We start with a reductive process to preserve fruit translation. Then we start the fermentation in tank, and as soon as it’s going we transfer it into neutral barrels and ferment it for about a month. After the fermentation is complete, we’ll stir the barrels weekly for about four or five months, which is key for this wine. The stirring of the yeast lees (the sur lie batonnage) is a process that will slowly erode the fruit presence, but will develop texture and midpalate to the blend. As those two things are working, we’ll find a point that we’re happy with it and finally bottle it. The balance they achieve in Bordeaux with the more textural polish in the midpalate is from the Sémillon and the brighter notes are from the Sauvignon Blanc. But when we started doing this, we didn’t yet have the Sémillon; and that’s where the sur lie batonnage came in. It’s actually a Burgundian technique that they use in Chardonnay production, but we borrow it and found it be very handy in this particular case.

NM: Then, in clear departure from Bordeaux varietals altogether, you also make Syrah.

JC: The Northern Rhône is more unique to producing just Syrah with small amounts of Viognier that they’ll blend in. Guigal is the producer that most people identify with in that area. And so, we try to mimic both our approach to growing the fruit and making the wine, though ours is a little more fruit-driven, maybe more smokey than meaty, and with not as much of the exotic flavors but just more pure Syrah. We make a wine where we co-ferment the Viognier and Syrah together — a technique that Guigal uses in some of his wines. The owner and I had had a conversation about it and he’d said how much he appreciates Guigal, so I told him that since I’ve used that technique in other places, we could try that. And so we did in 2003 and it was a success. But this is a case where’s much more difficult for Ron to make this happen than for me. The challenge is getting [the two varieties] on the same day!

RR: Viognier ripens much sooner than Syrah. If you want to get Syrah ripe, it takes a longer time than it would for the Viognier. So, we do a number of things in the vineyard to delay ripening on the Viognier until the Syrah is ripe and ready to pick.

JC: Luckily, we have someone as skilled and technically versed as Ron who can apply these techniques.

Fulfillment of a Promise: Showcasing Wines of Style & Longevity

NM: But, of course, skill isn’t the only thing going on here — there’s a great deal of artistry, too. And these are things that you both have in spades! Bringing this all full circle, then, what would you say that you’re hoping to achieve that you feel really separates Spring Mountain Vineyard from any other typical Napa mountain brand?

JC: I’m not sure that there is a typical Napa mountain brand. I think mountain Napa is a phenomenon that has developed over the last ten or fifteen years. People are finally identifying that there’s a difference between the mountains and the valley floor. And the valley floor is wonderful; I have no problem there. It’s a bit like comparing peaches to apricots to nectarines: they’re different things and each should be appreciated for their own qualities. But I do think that the whole Spring Mountain District is a unique experience from the standpoint of its wines — because of their structure, because of their fruit forward quality, because of their ageability. Those things resonate as commonalities among all the producers here. Ours are unique, though, because we’re on the side of the mountain and have so many different vineyard blocks with so many different exposures. We can come up with an incredibly layered and integrated wine like the Elivette because we have all these elements that we can interlace and make something that’s complex, interesting, and long-lived that will allow people to enjoy over a long period of time.

Style and longevity. Together these are, without a doubt, the hallmark of Spring Mountain Vineyard wines — and, as it were, of the very talent that produces them. To learn more about this producer, its story, and portfolio, visit Spring Mountain Vineyard online.

Interview by Nikitas Magel

Photos by Spring Mountain Vineyard

Comments are closed.