Elevating Elegance

Winemaker Interview

Elevating Elegance

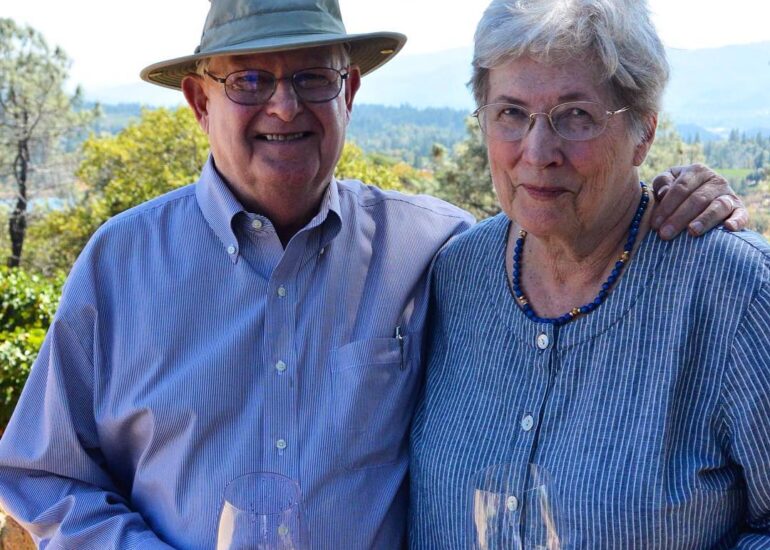

A conversation with Robert Craig and Stephen Tebb of Robert Craig Winery on Napa's Howell Mountain

Napa Winery Carves a Niche in Showcasing Cabernets from Elevated Vineyards

An Interview with the Founder and Winemaker of

Robert Craig Winery

Expression. Location. Distinction. These, we might argue, are the core elements of a finely made wine — one that conveys a message from a particular place with a unique identity. With its wide variation of climate, soil, and topography, the north coast of California affords vintners a nearly limitless collection of stories to tell in the making of their wines. One producer in the Napa Valley has taken to doing so from a rather lofty vantage… quite literally. Robert Craig Winery focuses on crafting Cabernet Sauvignon from small vineyards located on three of the mountains that define the region’s perimeter. With rigorous vineyard management and meticulous winemaking, this producer has managed to highlight the singularity of its featured appellations with stellar wines made from fruit raised on Howell Mountain, Mount Veeder, and Spring Mountain. On a mission to get to the bottom of this top-performer’s story, I sat down with the proprietor himself, Robert Craig, and his winemaker Stephen Tebb, in the bright and airy tasting salon of his recently built winery, with a view of the valley below.

While his eponymous brand was established somewhat later in his career, Robert Craig is a seasoned veteran of Napa’s wine industry. Having started out by directing vineyard development and managing initial winery construction for The Hess Collection, Bob became intimately familiar with mountain grapegrowing long before setting out to make his own wines. By then, he had already decided to focus not only on the production of Cabernets from hillside vineyards, but to impart a textural elegance and fruit expression to these wines that for so long bore the reputation of being unapproachable in their youth. With the erudite guidance of consultant Keith Emerson and, more recently, winemaker Stephen Tebb, Robert Craig Winery has succeeded in its mission of not only carving a niche by featuring wines from Napa’s mountain appellations, but in doing so with panache, by polishing their personality and highlighting their singularity.

— Nikitas Magel

Following are edited excerpts from the interview. At the bottom of this post is the full recording.

Planting the Seed

Nikitas Magel: You’ve managed to establish Robert Craig as a highly respected wine brand in a relatively short length of time. But how did this all begin?

Robert Craig: Increasingly, more and more people are coming into the Napa Valley from other parts of the country or even the world. But when I first got started, people assumed (often rightfully) that if you’re making wine in Napa then you’re from California. I was actually born in a mining town in Arizona and grew up in South Texas, then later came to California while in the Coast Guard. I really loved it here. After I got out of the service, I went to school and met my wife Lynn. We used to come up to the Napa Valley — back in the ’60s, when there were only eight or nine wineries! {laughter} What most people don’t realize is that Robert Mondavi, in 1966, had been the first new winery established in the Napa Valley since Prohibition, which marked the beginning of the second era in California’s wine industry. But, anyway, after going to school in San Francisco, I went to the University of Chicago for a couple of years [of grad school]. Coming out of there, I thought, “With this MBA, I’m going to get a really great job in the wine business!” But the reality was, I couldn’t even get a job! At that time, there were mainly small wineries that were all family owned, and apparently all the good jobs went to family members. On top of that, there was apparently no place for marketing in the industry; I actually had the president of a then-major winery say to me, “Your background is in marketing. We sell everything we produce, so we don’t need any marketing!…” {laughing} I now like to think of that as a great time-capsule comment: nowadays, grapegrowing and winemaking is only half the battle; marketing is the other half. You have to be successful in both in order to be successful at all.

RC: The real shift for me came when I began working in real estate. With that, I ended up in an asset management company in San Francisco as a real estate specialist. A colleague and I did a study on vineyards as a form of partnership investment. We soon decided that that what we really wanted to do, so we quit our jobs and put together an investment group. By 1978, we finalized the purchase of a 300 acre vineyard property up on Mount Veeder that was partially planted — it had about 20 acres of vines and was prepared for another 40 acres. The group had owned the property for about three years when Donald Hess came to Napa on a visit from Switzerland. He actually came to look at the water [in consideration of a bottling facility], but he ended up not liking the water at all. On his way out the valley, though, he and his team stopped at a little restaurant for lunch and had some wine — and that he did like! Donald discovered the Mount Veeder vineyard we were managing, and then purchased it. He asked me to stay on as general manager. For the next ten years, I worked intensively with mountain vineyards and learned a lot.

NM: So you really began your wine career as a commercial grower selling grapes for Hess.

RC: Yes, from about 1978. And then in 1982 we did a little bit of experimental winemaking — but nothing serious, less than a thousand cases.

ST: {to RC} So, you took Hess from ground zero to 1990…

RC: Those were the real beginning years of developing vineyards and starting a brand. At the same time, we had all of the construction going on to build the winery.

NM: What led you to leave Hess, after a decade, and go off on your own to start your own brand?

RC: A couple things. By that time, after doing something for ten years that I really poured myself into, I thought it would be really nice to have my own brand. I also think that Hess was heading in a different direction. He was just introducing his Select wines, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to do that. Plus, when I left there, I had a real stroke of good luck. Someone was planting a vineyard up on Mount Veeder, and they had a sense it wasn’t going quite right, they asked John Shafer to recommend somebody to complete the vineyard, and he recommended me. The owner is a well-known entertainer who wasn’t interested in going out and presenting wines. He just wanted to have a place in Napa, and I think his interest in the vineyard was more to help pay for the property. So, I established the [Pym Rae] vineyard in 1991. It was kind of a handshake agreement: if I planted the vineyard, I’d be able to get the grapes. And it’s been a really good relationship; I got to be extremely good friends with the guy who manages the property — Brian Nuss. He and his wife Lori have their small brand, Vinoce, and so we’ve been getting grapes from that same vineyard. At the same time, I’d become really good friends with winemaker Dennis Johns of White Cottage Ranch on Howell Mountain. When I started making wine, Dennis helped to sort out our wine style and introduced me to Howell Mountain fruit.

Refining the Brand

NM: Interestingly, it sounds like you were clear very early on about the wines that you wanted to make, as far as the vineyard locations and their appellations.

RC: When we started our own brand in 1992, it was just a Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon at only about 300 cases. We were still in the process of defining what we wanted to do, and so I’d made some experimental wines from different parts of the valley — that’s how I ended up on Howell Mountain. The program really came together about a year later, in the sense that we knew we were going to make both a Mount Veeder and a Howell Mountain Cabernet Sauvignon. Those two [appellations] were in our minds from the very beginning. But then as we thought about an overall wine program, we figured that since those were mountain wines, we might also want to make a Bordeaux-style Cabernet from the foothills, which we could offer to good restaurants as an elegant, versatile wine: the Affinity Cabernet.

But we weren’t just focusing on the vineyard locations; it was also about the wine styles. When I first started in the business in 1978, mountain wines almost had to have a consumer warning on them, about all the things that could happen if they dared try to drink the wines within twenty years! {chuckling} Because with mountain wines back then, there was a lot of really beautiful concentration and depth of flavor, but on the other hand you also had these massive tannins. I guess the objective we’ve always had was to bring those components together, to keep the things you do want — all the power and concentration — but to work with the tannins so they’re riper, rounder, more balanced, and really integrate with the rest of the wine. That was our stylistic objective from day one.

NM: These days, we don’t here quite as much talk about mountain or hillside wines being so aggressive with their tannins. I wonder if that’s because the local wine industry has learned so much in the last few years about vineyard management and winemaking to make these wines more approachable earlier on.

RC: I think that’s true. And I also think that wineries realized that [waiting for tannins to soften over time] is not how wine is consumed, for the most part. People in this country don’t have huge cellars where they can age wines that might otherwise be unapproachable early on. Of course, there are still producers making wines in a style that requires some aging before you can drink them, and I think those wines do have their place. But for my own interest, I really like to be able to experience wine over a period of time, one that I can drink when it’s young — even though it might not be fully integrated and its tannins might be more prevalent — and then at later intervals of aging. It’s fun to see a wine progress over time.

NM: You’ve got a great representation of Napa Valley’s elevations, with the three mountain sites — Howell Mountain, Mount Veeder, Spring Mountain — and the one valley foothills site, Affinity.

RC: It’s interesting how that’s evolved over time. But what it emphasizes is the sheer diversity just alone in the Napa Valley. I was at a viticulture seminar a couple of years ago, and there was a soil scientist presenting who told the group that there are 46 different soil types in the valley. I mean, we’re talking about an area only 30 miles long and 10-15 miles wide, and it has more soil types than all of France! Which is why we can have so many wines here that have a real sense of place. The common element with these three of our wines is that they’re all mountain wines. But let’s go back to what makes a mountain wine what it is. It’s a fairly simple thing: in the mountains, you have steep slopes, so when it rains, the water washes off the mountain and not much of it stays in the soil. Even with the drip irrigation as we have in all of the vineyards, over the growing season the vines never get as much water as they really want. So, without the roots taking up much water, there’s real concentration in the juice of the berries, and that’s what gives us concentration in the wines. That’s one common element across all the mountain wines. Another common element, because of that water restriction, is that the grapes end up being very small, like blueberries. So, the ratio of skin-and-seeds to pulp-and-juice is very high.

NM: Those are striking qualities — all in common among the mountain appellations represented in your portfolio. But how would you compare them and describe their differences?

RC: Comparing the Mount Veeder and Howell Mountain, I think the primary difference is in the soil. Mount Veeder is actually an ancient ocean bottom that was pushed up, and so it’s decomposed sandstone with a subsoil of petrified shell — it’s an amazing thing to see. Also, being on the west side of the valley, Mount Veeder has more of an eastern exposure to the sun. But on Howell Mountain we’ve got volcanic, mineral-rich soils, with an overall western exposure. So, in many ways, the two are very different, and that definitely comes out in the wines.

RC: (con’d) Now, when we were thinking about doing a Cabernet from Spring Mountain, I was really concerned because our entire wine program is based on what’s different about where the grapes come from. I initially thought that Spring Mountain, [also] being on the Mayacamas, would be too much like Mount Veeder. But when we finally made the wine, we discovered that it actually had a totally different personality! What we realized is that Spring Mountain has the climate of Mount Veeder but has the soil of Howell Mountain. And it ends up making for such a unique flavor profile.

ST: I worked with Howell Mountain fruit also when I was at Artesa. The way I think of it, specifically in the context of the Spring Mountain and Mount Veeder fruit, doing verticals and lots of tastings, is that the Howell Mountain wines have a really high-toned characteristic with a savory quality. There’s certainly also a sense of place — you can spot it in a blind lineup almost every time! It’s very rocky, volcanic soil, so the vines really do struggle. The tannins are definitely an issue here, but in keeping consistent with the house style, we worked to round out those tannins and make them more integrated and approachable. Nonetheless, they’re still there, they’re evident. But to compare it to the others, I think of it as being a high note, one that’s more highly strung, whereas the Mount Veeder wine is more of a bass note.

Tailoring Techniques

NM: Speaking of which, even though you’re making wines from three distinct Napa mountain appellations now, Bob, you mentioned you have a soft spot for Mount Veeder. Tell me about that.

RC: When I was considering what to do in the wine business, I’d been doing a lot of tasting at the Vintner’s Club in San Francisco, which is a really fabulous organization that has some great tasting events. What I discovered there was that the more I tasted mountain wines, the more I liked them. But I especially loved the Mount Veeder wines. At that time, Mount Veeder Vineyards was making a steller wine — one of the most gorgeous wines I’ve ever tasted — and it inspired me to want to grow grapes and make wine from where it came from. What I’ve always loved about Mount Veeder is that you can make a really powerful mountain wine with all the concentration and depth, but if you make it in a certain style, it has elegance too.

A minute ago, I mentioned the complexity of the soils and how that contributes to different locations in the valley coming through in different wines. But another really important component is micro-climate. What’s really wonderful about the mountains is that with the upheaval of the soil, you have all these different exposures — sunlight exposure, wind exposure, soil type, soil depth — you just have so much going on that there’s a built-in complexity.

Generally, when I talk about mountain vineyards, where you have absolute diversity, I usually contrast them to those on the valley floor, where you have absolute consistency. For our winemaking techniques, the mountains work really wonderfully because we like to pick about four to eight tons each harvest day and have that as a separate fermentation lot, because the fruit ripens at different periods. In a valley floor vineyard of, say, about 20 acres, you’re probably going to pick it all in about a week or so. On the mountain, we’re harvesting [in waves] over a period of five or six weeks. It’s great because Stephen can see what’s in a particular lot, and ferment it accordingly. If it’s really beautiful and fairly light, we might feel that it won’t hold up to the tannin extraction late in fermentation and decide to take it off the skins and finish fermentation in barrel. But if another lot is really powerful, we might feel that it can go all the way through, so we’ll ferment it to dryness and perhaps even do some extended maceration. And so at the end of fermentation, we have a cellar full of these different wine lots [from a single vineyard].

NM: What have you learned in making the wine from one appellation that has compelled you to reevaluate your choices or assumptions in the making wine from a different appellation in the portfolio?

ST: The process is ongoing. Even though we have a well-developed knowledge of what works, we’re constantly reassessing everything, always hanging a question mark on all that we do. That’s part of the fun of winemaking — it’s intriguing, it’s always a puzzle, every year is different. We know what’s worked in the past, we know the basic framework, and certainly we do borrow from some of the other styles in the portfolio when making a particular wine. But in general, we’re always questioning assumptions in winemaking. We’re also constantly looking at what worked and what didn’t, why something worked in one vintage but not another. There’s a wide degree of variability that happens in any given year, a lot of which is weather-driven, which has us always reevaluating things that we do. We know what definitely works, but we’re always seeking ways of improving the process and making the wines even better than they are now. And the changes we might make are small and incremental.

For example, in evaluating the fruit from the three mountain vineyards — Howell Mountain, Mount Veeder, Spring Mountain — we decided to bottle the Howell Mountain Cabernet sooner than the other two. That’s because we wanted to really capture the floral, spice, and bright fruit qualities of the wine, as opposed to possibly losing some of those more delicate nuances by having the wine sit longer in barrel. We really wanted to highlight those features, so we got it out of barrel sooner rather than being formulaic about it by allowing it to sit for the same length of time as the others. And we did that with Keith’s influence; having been through all this for the last four vintages, he’s got a really good understanding of what can be achieved in our wines.

RC: Yes, usually the changes we make really are small steps. But one really big one we took about four years ago was to no longer filter the Cabernets. And that’s one of the things that Keith has brought to the general winemaking — more gentle handling along with really focusing on retaining the things you want in the wine and not extracting those you don’t.

NM: On the one hand, you’re needing to keep sight of all that’s fairly standard in winemaking, but on the other hand you’re having to stay on your toes and remain open to unexpected variation brought about by the vintage itself. How do you know where to draw the line, how to strike that balance?

ST: It’s a day-in-day-out job! You wake up in the morning and you start thinking about these things. But to get back to broad picture, there are certain ways of going about making wines in the Napa Valley and they’re there for a reason — they work, they’re successful. But being open to new ideas is critical. As soon as you close yourself off, you’ve lost the game right there. You mentioned earlier that there are increasingly new ways of thinking about wine among winemakers, one example being how in the last few years they seem to have a better handle on managing tannins and making wines more approachable — all of that is the result of discussing ideas with other winemaking colleagues and of being open to constantly improving wines by trying out some of those ideas. That’s how it all comes about and that alone is really a full-time job. We can’t simply say, “We’ve been doing it this way and that’s how we’re going to continue doing it.”

RC: A good example of that is the managing of temperatures during fermentation. You almost pretty much have to do that lot by lot and day by day. Honestly, when we began, we thought we’d want the wines to emphasize the beauty in the fruit, so we’d have fairly low temperatures during fermentation — maybe 75-80ºF. But that’s too simple. Sometimes we really need to run up the temperature and then decide how long to hold it there. That’s real winemaking, because it’s not done by rote; it’s done wine by wine.

ST: None of this is formulaic. We need to make decisions in real time, when they’re happening, when the ferments are occurring, we need to be tasting and evaluating, and in large part relying on experience. Bob has a lot of experience and history with the fruit; he’s got a really good sense of things. To arrive on the scene and be a winemaker on day one — it doesn’t work that way; it takes time to develop your palate, it takes time to recognize these things before you can really get a sense of what might work.

NM: At its most rudimentary, winemaking occurs in two very different contexts, each of which has its own constellation of variables that you can influence or change: the vineyard and the cellar. What is your take on doing things out in the vineyard versus doing them in the cellar, as a way to really coax the wines to where you want them to go?

ST: We make the wines in the vineyard; that’s really our focus. The less we need to do in the cellar, the better. Sometimes we have to do stuff in the cellar to get the most of what we want. But making the wine is all about growing the grapes. You do your job first in the vineyard, and what you do in the winery is to layer on top of the success you already have from the vineyard.

RC: I think winemaking begins at budbreak. What Stephen brings, which I think is really great, is his viticulture background. There hasn’t always been a good interface between the vineyards and the winery, so I stepped back into the process around five years ago and started working directly with Carlos Mendez [our vineyard manager] to specify what we needed to do with the vines in order to make better wines. And he really bought into the process — he invites Stephen and Keith out to the vineyards to provide direct input and advise on what we can do to make the very best wine. Carlos is much happier now because he feels that he’s integrated into the whole process and taking responsibility for the wines’ quality.

NM: Speaking of vineyard management, what have you learned in all this time that has challenged and even changed some prior assumptions about farming, be it specific methods or overall philosophy?

RC: It’s interesting, when I first got into this some time ago, the big thing was leaf-to-berry ratio. When the move for tighter spacing [in the vineyards] came about, the emphasis turned to more vertical training [of the vines], so everybody started doing it. And we got caught up in that for a period of time. But then we started to rethink whether it was really a good idea — because the more vertical training you have, the more leaves need to be removed, which then exposes the fruit to more direct sunlight. We discovered that what we really wanted was not direct but filtered sunlight, especially on 100+ degree days. And so we realized that what we’d been doing long ago had actually been better for the fruit. So we installed cross-arms and tried to spread out the canopy and give the fruit more protection from the sunlight.

ST: Which means the vineyards don’t look as tidy, with a lot less of that perfectly linear and upright appearance. There had been a big move away from the ‘California sprawl,’ or big-bush shape from the old days, towards the concept of the vertical shoot position, which was very neat and tidy. Everyone loved the way it looked. But what we’re finding — and not just us but this is really the latest thinking in viticulture in general, some of which was driven by the temperature events we’ve had over the last several vintages where some of the fruit was sunburned — is that some shading on the fruit is really beneficial. That said, there are some areas where the vertical training works beautifully, but that has to evaluated on a site-by-site basis. If you’re growing Chardonnay on the coast, you need those vines opened up [to maximize air flow and minimize fungal growth]; but if you’re growing Cabernet up on a mountain, you don’t need that!

Looking Ahead

NM: Witnessing these sorts of changes in the thinking and practice of viticulture and winemaking, what is your sense of the direction that the overall industry in Napa has come thus far? And what are your thoughts about where it might be going in the future?

RC: I think that wines coming out of the Napa Valley have improved remarkably over the years. When I first started, there were a lot of wines that really weren’t all that good. But that can’t be done anymore; at a certain price point, there’s an expectation that a wine is going to have great fruit expression and wonderful texture, and that makes it all very competitive. That’s why all of us here have to keep tweaking the wines — we want to stay among the top group of wines from Napa.

ST: The competition is fierce. There are some great wines being made in Napa. You may find some that don’t inspire you, but technically you’d have a hard time finding wines here with basic flaws — you don’t see that sort of thing anymore.

NM: In many ways, I get a sense that this immediate region — namely Napa and most of Sonoma — is coming out of its pure discovery phase and is really starting to focus on site specificity. Producers are now, more than ever before, thinking critically about what works in terms of varietal choices and viticultural methods for individual sub-appellations and even specific sites, tailoring them instead of employing the one-size-fits-all approach from earlier days.

ST: I think we’re getting closer to what European regions have long been doing.

RC: When I first came to the Napa Valley, there were vineyards that had everything from Riesling to Gamay Beaujolais to Petite Syrah — they’d have ten varietals in one vineyard! In the old days that worked because the buyer was usually some very large winery, like Gallo, who would make all sorts of different wines. But what’s happened over time is that things have focused down to thinking about what’s the very best varietal for a specific terroir. I think where you really see the increase in terroir specificity is with Pinot Noir. It wasn’t too long ago that I didn’t really care for many California Pinot Noirs. But they’ve come a long way and producers are really refining how to work with that grape and where to grow it. And here in the Napa Valley, I think that focus on terroir is why Cabernet is king, because this is really the place for Cabernet Sauvignon.

And it’s with that very focus on a sense of place that, until his death in 2019, Robert Craig himself succeeded in carving his own niche with the noble varietal for which Napa has become so well known. By applying the concept of terroir to the region’s mountain Cabernets, his team continues to showcase a collection of special wines, each with their own unique character and personal story. To learn more about Robert Craig Winery and its portfolio of wines, visit Robert Craig Winery online.

Interview by Nikitas Magel (originally recorded in 2010, updated in 2024)

Photos by Robert Craig Winery

Comments are closed.